Investigation Report: A Review of political control over cannabis Pt. 1

- Jul 11, 2025

- 32 min read

The Skunk Narrative: Purpose, Management and Beneficiary

Prepared by Cefyn Jones, The Hemp Hound Agency / The Shadowroot Network

Background

Ever since 2018, I’ve had questions about the management, intent, and direction of cannabis in the UK.

And for context, I mean cannabis in a collective sense from consumer dynamics to industrial use.

You might recognise that year for the legalisation of medicinal cannabis, and for press reports suggesting that certain politicians’ spouses stood to benefit from that legalisation. But for me, there was something deeper going on.

As a former worker for the UK’s largest trade association in the hemp and CBD sector, I was just behind the front lines of conversations involving multiple regulators, politicians, and industry stakeholders. I watched intently as the CBD Novel Foods fiasco unfolded.

Then came The Hemp Hound Agency — and with it, a position arguably on the front line itself.

In 2022, I decided to do more than ask questions. I submitted a formal complaint to the Food Standards Agency (FSA) regarding its management of the UK hemp and CBD industry under Novel Foods.

It was the handling of that complaint that made me realise something: the process had clear similarities with the methods used to maintain cannabis prohibition.

And I further realised that both appeared to benefit a single company — one with long-standing ties to politicians whose husbands stood to gain from the legalisation of medicinal cannabis.

That led me to investigate the political control of cannabis in the UK — a journey that has involved reviewing hundreds of documents, tracing parliamentary careers, submitting dozens of FOI requests, and spending a great deal of time following paper trails that stretch back decades.

The cost to The Hemp Hound Agency has been significant — but I hope my efforts lead to something worthwhile: a proper public conversation about cannabis, involving the very people most affected by decades of mismanagement — the public.

This Report

This report — presented in three parts — outlines the key findings of my investigation.

It also recounts my personal and professional journey through the timeline.

Furthermore, elements of the story you’re about to read have already been dramatized on the big screen — albeit with the truth buried beneath the script.

Before we begin

A wise barrister helped me understand something important about the information I’m about to present.

He told me:

“What you have to determine is whether what you’re seeing is immoral or illegal — because immoral isn’t necessarily illegal.”

And that stuck with me.

But in a political context, we also have to ask:

If it’s immoral — does it serve the public interest?

I believe, whole-heartedly, that illegal acts will be described in this report. But I’m not a legal professional.

I am, however, a human being — and a member of the public. And I believe this investigation also reveals immoral acts. And that makes them our concern.

Because when government, regulators, and industry cross moral lines in ways that affect public health, public perception, and public policy — we have a right to know.

In late 2023, three FOI requests were submitted to the Home Office requesting:

Their response:

Strange, right?

And for context:

The request regarding petitions focused on cannabis and aimed to determine who holds the authority over petition decisions — the Home Office or the Petitions Committee — and whether any public interest tests were applied before issuing responses.

The request concerning Jacqui Smith and Gordon Brown also centred on cannabis, seeking communications that might reveal whether Brown instructed Smith to reclassify cannabis in 2008, regardless of the advice provided by regulatory panels.

Finally, the request about Cannabinoid Policy focused on CBD and Novel Foods, exploring Theresa May’s potential influence over the subject, and the appointment of an academic linked to GW Pharmaceuticals (GWP) onto a regulatory panel dedicated specifically to phytocannabinoids.

‘CBD Policy’ as a response didn’t make sense — CBD was only mentioned in one of the three FOI requests.

But the Home Office were just getting started. When asked to define CBD Policy, their response was:

So how do conversations between Brown and Smith — and how petitions are managed — relate to CBD Policy?

This means one of two things:

The Home Office deliberately blocked those FOIs without any real, justifiable reason, unless, CBD Policy existed as far back as 2008.

What’s more, the person at the heart of that early policy moved from the Home Office to become CEO of the FSA in 2019 — arguably to implement it.

That’s supported by the fact that the Home Office refuses to release any documents from 2014–2015, claiming it’s still active policy — and that policy makers need a safe space to do their thing, even when that thing may not be in the public interest.

Meanwhile, when asked directly, the FSA stated that they hold over 1,100

documents relating to CBD Policy between 1st October 2022 and 12th October 2023.

So tell me — How can there be over a thousand documents on a policy that supposedly doesn’t exist in writing?

Unless, of course…the policy isn’t written. It’s carried.

And if that’s the case, Emily Miles isn’t just enforcing CBD Policy — she is CBD Policy.

But she was also Director of Policing between 2012 and 2015, which means she likely had influence over the Skunk Narrative, and in directing multiple police forces in 2014 to supply GWP with samples of seized cannabis.

And when you read further, you’ll see: some of those samples were far from small.

We’ll be unpacking that in much more detail in Parts 2 and 3 of this report.

At the heart of this investigation — and the reason behind those FOI requests (and many more) — is a single critical question:

Has the UK Government enabled and maintained a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) that unfairly benefits GWP (now owned by Jazz Pharma) to the detriment of consumers, SMEs, and the cannabis sector?

Because when you look at how cannabis has been managed in the UK — and how GWP has consistently benefited from political intent and regulatory manoeuvring — that’s the only thing that makes sense.

And I say that as someone who’s been around cannabis in one way or another for nearly 40 years — with both personal and professional experience to draw on.

The simple answer is 'yes', as can be seen on page 108 of Prof. Geoffrey Guy's A Worthwhile Medicine (2021):

"The narrative WE maintained..."

That line says it all.

I would argue that no single corporate entity would be allowed to control a national narrative — especially one concerning something as publicly significant as cannabis — unless some form of agreement was in place.

A Public-Private Partnership (PPP) fits that description.

Admittedly, I didn’t come across Prof. Guy’s book until late 2024. But there were already plenty of other indicators suggesting the existence of a PPP — as you'll see throughout this report.

But think about this for a second:

How does a private company gain that much influence over the Home Office — and over cannabis regulation — seemingly from the moment it launches?

And the follow-on question:

Does that influence still exist today?

This report aims to answer both.

It also shows how the Skunk Narrative has been used to protect that PPP — to shut down any attempt at a broader public conversation about cannabis in the UK.

And it dissects the structure and intent of CBD Policy, exposing deeper issues with the FSA’s management of the CBD Novel Foods process — including how it is being used to create a cartel market, and how a complaint challenging that process was dismissed by the very author of the policy, without any declaration of interest.

For context

Below is a diagram that best describes how PPPs functions.

At their core, Public-Private Partnerships are about awarding a state-sanctioned monopoly — and behind that monopoly sits management by politicians and civil servants, who ensure the following:

Regulatory access

Public resources are provided when necessary

Legislative change is affected when needed

Competition is micro-managed to protect the monopoly

And behind them, you have the entity holding the monopoly — telling those politicians and civil servants what they need, while managing the public narrative to ensure compliance or distraction.

You might have noticed Step 5: Sell-On in the diagram. There are multiple PPP models — and they don’t necessarily end when the original holder sells the operation.

That means public resources, or regulatory influence, may still be needed to meet certain goals — even if the name at the top of the structure changes.

And just to give you an idea of how absurd it can get: I’ve seen one unrelated healthcare-sector PPP that change ownership 27 times — while the public still footed the bill.

As for cartel markets

CBD Policy is designed to benefit GW Pharmaceuticals and British Sugar, while the CBD consumer product industry threatens to undermine that monopoly by normalising access to cannabinoids as food — not medicine.

In response, the FSA has run a process designed to benefit a select group of chosen players, while actively disadvantaging the SMEs who built the industry from the ground up.

And by chosen, I mean those willing to accept the constantly shifting conditions of market entry — as the FSA has moved the goalposts repeatedly over time.

These chosen few have the financial backing to survive those shifts — long enough for the “riff-raff” to be cleared out — at which point the crumbs falling from GWP’s table might become more substantial, but only if GWP allows it.

So why is a cartel market necessary to protect GWP’s monopoly?

Simple: GWP hasn’t entered the supplement space.

But as you’ll see throughout this report, there are signs that such a move might be, or have been, in the pipeline.

In the meantime, GWP remains a pharmaceutical company — and there’s far more profit in medicines than in foods. But if people are using foods as medicine, that eats into future earnings.

So to protect those interests — which extend beyond the UK into the EU, US, and other jurisdictions — regulation is framed as “necessary.”

We now have Novel Foods regulation in both the UK and EU. But despite operating under the same framework, the process is being applied very differently in each region.

The US, meanwhile, appears to be preparing its own version — at both state and federal levels — although we’ve yet to hear whether that, too, will be shaped by data from Epidiolex, just as the Novel Foods process was when it launched in 2020.

And despite all this regulation being justified on the grounds of consumer safety, there’s one very inconvenient fact that tends to be left out:

Historical consumption of hemp — which contains both CBD and THC — has been widely accepted, and it has an exceptional safety record.

And when I say 'widely', that includes by the likes of the FSA, EU, and FDA.

In fact, it’s so safe that the FSA itself confirmed only one recorded adverse reaction to “hemp oil” between 1997 and the present day.

Please be aware

This is Part 1 of 3, and it compiles information I’ve obtained over the past three years.

Part 2 will focus on the creation and management of “CBD Policy”, and Part 3 will explore the implications of that policy — particularly the FSA’s handling of CBD Novel Foods, and how a formal complaint and a clear conflict of interest were effectively dismissed in order to protect it.

Together, these three articles will form the backbone of a more academically structured report, which will be submitted to all named government departments and actors for comment.

And for those still uncertain about the link between GW Pharmaceuticals and Jazz Pharmaceuticals:

You’ll shortly come across a document from Jazz that proclaims a relationship that would be legally impossible — unless GW Pharmaceuticals still exists as a functioning entity.

That continued existence is confirmed by a 2021 FOI response from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, which references direct communications with Jazz Pharmaceuticals, stating that GWP remains active to maintain academic and regulatory relations.

Glossary:

ACMD – Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs

ACNFP – Advisory Committee on Novel Foods and Processes

BEIS – Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy

CBD – Cannabidiol

CoT – Committee on Toxicity

DBT – Department for Business and Trade

EU – European Union

FDA – Food and Drug Administration (US)

FSA – Food Standards Agency

GWP – GW Pharmaceuticals

MDR – Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001

MHRA – Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

THC – Tetrahydrocannabinol

VMD – Veterinary Medicines Directorate

Terms

ADI – Acceptable Daily Intake: The maximum recommended amount of a food or compound (e.g. CBD) that can be consumed daily without appreciable health risk.

Article 4 – A formal submission to determine the novel status of a food in the UK or EU.

Controlled cannabinoid – Cannabinoids subject to the MDR, such as delta-9 THC and CBN.

Novel Food – A food (or food ingredient) that was not consumed to a significant degree in the UK or EU before May 1997.

Non-Novel Food – A food with a demonstrated history of significant consumption prior to May 1997.

Novel Foods (Process) – The regulatory application process used to assess the safety and authorisation of a novel food before it can be marketed.

Novel Food Regulations – The overarching framework governing novel foods. These can be interpreted or amended depending on the specific nature or format of the food.

Novel Status – The classification of a food as novel or non-novel, based on its history of consumption before 15 May 1997.

1mg Rule – Under Regulation 2, Limb C of the MDR: if a product contains less than 1mg of a controlled cannabinoid (e.g. THC or CBN) per container, it is exempt from being classified as a controlled drug. Exceeding 1mg renders it subject to full control under the legislation.

The Skunk Narrative: Purpose, Management and Beneficiary

To understand CBD Policy, we first need to look at the Skunk Narrative — because before there was CBD, there was “Skunk.” And as we've already seen in A Worthwhile Medicine, narratives around cannabis were not just reported — they were actively managed.

While writing this, I came across a particularly insightful piece: Making Sense of Politics: What Does Narrative Mean?. It maps out how political narratives are constructed, why they’re repeated, how they shape belief systems, and crucially — how they eventually become ineffective through overuse.

It’s a roadmap. One I hadn’t found until recently, but it helped me put a structure around what I’ve been observing for years — and confirmed my growing suspicion by 2023 that what we’re dealing with isn’t just poor policy, but a PPP protected by narrative.

...

1997

September: The MS Society and Royal Pharmaceutical Society host a conference on the use of cannabis for MS sufferers.

Prof. Geoffrey Guy attends. According to A Worthwhile Medicine and The Medicinalization of Cannabis, he was supposedly “retiring” at the time — yet he not only shows up but offers detailed commentary on how to stabilise a cannabis extract, formulate an effective product, and how regulators might authorise it for market. This, despite no publicly known prior experience in cannabis pharmacology.

November: Prof. Guy attends a meeting at Parliament chaired by George Boateng, then Disabilities Minister, where it’s announced that the government is seeking research into the medicinal potential of cannabis. This research would be overseen by the Home Office and the Department of Health and Social Care.

Before this, Boateng served as a Treasury spokesperson.

While the meeting reportedly included academics, researchers, and physicians, there’s no evidence of any open competition or bidding process for the research contract the government was preparing to fund.

December: Prof. Guy submits a formal proposal to the Home Office — just before Christmas.

1998

January: Prof. Geoffrey Guy provided the Home Office with a 22-point plan to regulate and control cannabis in the UK.

In The Medicinalization of Cannabis (2010), he recalls how this came about:

No competition?

Notably, in the same retelling, Prof. Guy describes a candid exchange with the Home Office that hints at the absence of any competitive tendering process:

This quote, paired with Prof. Guy's earlier meeting with George Boateng in November 1997, strongly suggests that no open call for research proposals or commercial bids ever occurred. Despite the scale and implications of the project, no one else was apparently considered — or even asked.

June: A press release announces that GW Pharmaceuticals had been granted a licence by the Home Office to cultivate cannabis for the purposes of medicinal research.

In A Worthwhile Medicine (2021), Prof. Geoffrey Guy confirms that two licences were issued at the time — one to the company (GWP), and the other a personal licence issued to himself:

However, this raises a major inconsistency. The Home Office has gone on record multiple times — particularly when rejecting public petitions — to state that personal licences for growing cannabis for medicinal purposes are not issued, even to patients.

The fact that one was granted in 1998 — to an individual with commercial intent — undermines decades of later Home Office reasoning and rejections.

According to Companies House, the company that would become GW Pharmaceuticals was originally registered in 1995 under the name Titanite Limited. This indicates that there may have been commercial intent long before Prof. Guy's public appearances at the MS Society and Royal Pharmaceutical Society events in late 1997.

In A Worthwhile Medicine, Prof. Guy refers to this as just “an off-the-shelf company,” explaining that it was used because doing the full paperwork would have taken too long. Yet…

Titanite's existence two years prior to the supposed retirement-then-opportunity pivot suggests it may have been a placeholder — a signal of intent — and perhaps evidence of earlier engagement with government in an informal or private capacity.

Prof. Guy had at least five companies listed with Companies House at the time, so his comment about needing one ‘ready to go’ is not implausible — but in context, it feels like more than just preparation for “the next idea.”

October: Paul Boateng is appointed Minister of State for Home Affairs.

...

To note: To Note: Early Signals, Strange Gaps, and a Potential Pre-Built PPP

There are some intriguing data gaps from this period, and one standout curiosity: a man seemingly on the verge of retirement suddenly appears at a medical cannabis conference, laying out an entire product pipeline from plant to patient.

In The Medicinalization of Cannabis (p.35), Prof. Geoffrey Guy says he had to be reminded of an interest in cannabinoids dating back to 1982 — after obtaining his cultivation licence.

Earlier in that same source (p.34), he claims to have approached the Home Office in the early 1990s to discuss cannabis, only to be turned away.

But were they really not interested?

That same November, he's at a meeting in Parliament, chaired by then-Disabilities Minister Paul Boateng, where it’s announced the UK Government will fund research into the medicinal potential of cannabis. A proposal is submitted by Guy in December.

By January 1998, he provides a 22-point plan to regulate and control cannabis in the UK.

By June, GWP has a license, but according to A Worthwhile Medicine (p.105), this includes a second, “personal” licence — despite the Home Office’s repeated stance that personal licences for medicinal cannabis are not issued.

This all moved very quickly.

Prof. Guy refers to Titanite as an "off-the-shelf" company, suggesting it was set up in case something came along. But Companies House records show five linked companies — and taken with the 1995 registration date, it begins to look more like a signal of intent than a placeholder.

It also raises questions about what discussions were happening behind closed doors before the official narrative began.

A Question of Influence

If you’ve been following this so far, one question should be obvious:

How does someone convince the Home Office they can grow and process cannabis into a pharmaceutical product — from scratch — and do it to such a degree that they start managing the Home Office’s narrative around cannabis itself?

Because that’s what appears to have happened. This isn’t just about one man with an idea — it’s about access, influence, and trust at the highest level. And that kind of trust usually takes years to build.

In 2022, Jazz Pharmaceuticals submitted evidence to the Home Affairs Committee stating they had a 20+ year working relationship with the Home Office.

That’s strange — because Jazz acquired GW Pharmaceuticals in 2021.

So either that statement is factually incorrect, or GWP — and its privileged relationship with the Home Office — still exists as a functioning entity.

Which is confirmed in an FOI response from the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS, 2021): the government was still engaging with GWP directly post-acquisition, specifically for regulatory and academic liaison.

Waldegrave, the Timeline, and a Potential PPP

Now we need to talk about Lord William Waldegrave.

He was the UK’s first appointed head of Public-Private Partnerships, and served as Head of the Treasury — just before Titanite was formed in 1995. In September of that year, a cannabis farm was found on Waldegrave family land.

It was claimed the land belonged to his brother, who had died months earlier. But Companies House records from before his brother’s death show Lord Waldegrave was the majority shareholder in the family farm.

There’s further confirmation from January 1995, when he was forced to defend sending veal calves for slaughter from that very land — months before his brother’s passing.

That land was his.

Just months later, Titanite was launched.

Then, in May 1997, 19 days after Tony Blair’s Labour Government took office, a company called The Biotech Growth Trust was launched — its purpose being to manage shares in biotech start-ups. It would go on to own stock in both GWP and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Waldegrave was named a director of the company three days before the press announced GWP’s launch in 1998.

He later received shares in GWP worth the equivalent of $40 million (More in Part 2). Some of those were vested — meaning they became accessible only after key regulatory milestones were achieved.

The question is, which milestones did he help make happen?

Connecting Threads

If Prof. Guy’s version of events is taken at face value, the entire GWP venture — from concept to licence — happened in under seven months. That’s implausible. More likely, a longer and quieter period of negotiation and validation preceded it.

If so, the most plausible explanation is a PPP — one built quietly under John Major’s Conservative government, then signed in and accelerated under Tony Blair’s Labour government. That might explain why both parties remain so firmly aligned in supporting the Skunk Narrative — and why real discussion around cannabis policy remains so tightly managed to this day.

...

1999:

Sativex enters Phase I trials

2000:

Sativex enters Phase II trials

March: Derriford Hospital in Plymouth received £1 million in funding to test cannabinoid-based preparations on MS patients. This was part of a wider clinical trial involving other hospitals and up to 2,000 participants.

June: Paul Boateng was recorded in Parliament discussing the medicinal use of cannabis and its intersection with the Misuse of Drugs legislation.

Later that year, Professor Ben Whalley of the University of Reading published work showing that non-THC components of cannabis — specifically CBD and CBDv — inhibited seizure-like activity in rat brain tissue slices.

...

To Note: If you were to take the link for the University of Reading's relationship with GWP and place it in Wayback Machine, you'll see that there have been four edits in the last 9 months.

What's more, you'll see it wasn't archived until five years after it was published, and the reason why I bring that up is because I remember a different entry for 1996, specifically one that said something appetite related rather than just:

A psychologist at the University of Reading, Dr Claire Williams, became involved in research on the 60 compounds derived from cannabis, known as cannabinoids, including looking at whether any of them had potential for alleviating epileptic seizures.

We’ll be unpacking this further in Part 2, along with a wider concern about previously available information published by the University that now seems to have quietly disappeared.

...

2001:

Sativex enters Phase III trials

March: GWP was named in a Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) document for registering Plant Breeders’ Rights. While some have speculated that GWP attempted — or are attempting — to patent Skunk #1, registering for Plant Breeders’ Rights more likely suggests the development of a new strain, potentially a stabilised version of Skunk #1.

June: GWP was listed on AIM, the London Stock Exchange’s market for small and medium-sized growth companies. That same month, Paul Boateng became Financial Secretary to the Treasury.).

July: Lambeth Council launched a nine-month cannabis decriminalisation pilot project. Brixton police reported saving 650 man-hours by November by de-prioritising minor cannabis offences. Around the same time, Home Secretary David Blunkett announced plans to reclassify cannabis from a Class B to a Class C drug.

November: The British Medical Journal published an article titled Cannabis: The Wonder Drug?, revealing that cannabinoid research was taking place at a secret location in Sittingbourne. The strains identified were Northern Light, Hindu Kush, Gloria, and Skunk.

David Watson — also known as Sam the Skunkman and associated with Hortapharm, named in the 1998 press release — confirmed to The Hemp Hound Agency that "Skunk" referred specifically to Skunk #1. He stated that he planted the seeds for GWP’s first grow, that Skunk #1 seeds were used, and that a clone of Skunk #1 was specifically licensed to GWP for the creation of Sativex.

At the same time, the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (MDR) 2001 were being drafted. While the stated intent was to better regulate the transportation, testing, and destruction of controlled substances, the 2001 regulations included a strong focus on cannabis — introducing new definitions and formalising requirements for research and development sites.

Lord Gareth Williams, who was quoted in GWP’s 1998 launch announcement as saying that drug legislation would be revised upon meeting certain milestones, served as Attorney General until June 2001. Between 2000 and 2001, he participated in 13 drug-related parliamentary debates.

...

To note: There are several points in this report where seemingly peripheral figures begin to indicate that the timeline presented by Prof. Guy may not be entirely accurate.

One such figure is Lord Gareth Williams. Though his role might appear minor at first glance, had it not been for his untimely death in 2003, he may have played a far more central role in the narrative.

Williams was not a career politician. He became a Lord in 1992 following a highly successful legal career. In May 1997, Tony Blair appointed him as Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Home Affairs — a position he held for just over a month before being moved to Minister of State for Prisons, shortly after GWP’s public launch. Later, between 1999 and June 2001, he served as Attorney General, during which time he would have advised on the drafting of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (MDR) 2001.

When GWP’s launch announcement stated that Lord Williams had suggested cannabis legislation would be adapted to accommodate products proven to be safe and viable, it suggests his involvement wasn’t just supportive — he may have been part of the process from the outset.

The same might be said for Paul Boateng. His political trajectory is particularly interesting. After helping steward GWP’s early years from his position at the Home Office, Boateng returned to the Treasury in June 2001 — first as Financial Secretary (until May 2002), then as Chief Secretary (until May 2005). Notably, he was also a member of the Public Accounts Committee between July 2001 and June 2002.

That placement is significant. When you consider the full context, it becomes increasingly clear that a large portion of Boateng’s parliamentary career was spent nurturing GWP’s development and integration into UK policy.

I recently reached out to The Lord Boateng, hoping to have a conversation about the PPP that he helped shape. I like to believe people act with good intent, and I wondered whether he had lost sight of how far GWP had grown — or how their monopoly has affected the sector.

Unfortunately, despite sending my request to both his parliamentary and professional email addresses, I received no reply.

But this kind of strategic placement isn’t limited to politicians. As Part 2 will show, several individuals seem to have been positioned in key roles for very specific purposes.

...

2002:

The exact dates for the events in this year are unknown outside of them being recorded by the MHRA and Companies House.

The MHRA’s Yellow Card Scheme begins recording fatalities attributed to Cannabis sativa-based medicines — the first time such entries appear since the scheme began over 30 years prior.

According to a recent FOI response from the MHRA (Ref: FOI 2025/00108), these deaths were attributed to herbal cannabis.

This is highly peculiar, as there were no authorised herbal cannabis-based medicines or vaccines in the UK at that time. GWP’s formulations focused on stable, extract-based products, not herbal preparations.

The MHRA also confirmed that causality is often unproven within the Yellow Card Scheme. This means the two fatalities attributed to herbal cannabis in 2002 may have been due to unrelated causes — or potentially linked to non-medical sources.

Deloitte is also named as GWP’s auditor this year. This is notable because Deloitte would go on to manage the public sector arm of the Public-Private Partnership between GWP and the UK Government.

With an office based in Reading and a focus on PPPs, Deloitte’s deeper involvement in the regulatory infrastructure will become more evident in Part 2 of this report.

...

To note: If herbal cannabis was genuinely responsible for two deaths in 2002, why did the government proceed to downgrade cannabis from a Class B to a Class C substance in 2004?

Furthermore, how can the MHRA’s Yellow Card Scheme be taken seriously when causality in many cases is unverified?

Mainstream science broadly agrees that it is not possible to fatally overdose on herbal cannabis or traditional extracts.

And crucially, there were no authorised herbal cannabis medicines or vaccines — nor any known trials involving them — in the UK in 2002.

Adding to that, the government only recently recognised the medicinal value of herbal cannabis — a stance it did not hold at the time.

So, what exactly are we looking at here?

My belief is that this marks the beginning of a long-term effort to blur the lines around cannabis classifications — an effort that becomes more visible in 2018 (Part 2).

...

2004:

January: Cannabis is officially reclassified from a Class B to a Class C drug.

Later that year, GW Pharmaceuticals receive samples of seized cannabis from multiple police forces — authorised by the Home Office. (See 2008 for context.)

These transfers, and all those that followed, would have been facilitated under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (MDR) 2001, which was brought in with guidance tailored to suit GWP’s research and operational needs.

2005:

December: Prime Minister Tony Blair announces a U-turn on cannabis policy, citing a public outcry over so-called “strong cannabis” and Skunk varieties.

This moment marks a deliberate shift in the definition of Skunk: no longer referring to specific strains such as Skunk #1, Super Skunk, or Special Skunk, but instead to any cannabis above 14% THC.

As a grower at the time, I can confirm that by 2005, Skunk and its related strains were already considered old genetics — largely obsolete.

Moreover, the public had no access to THC testing at the point of sale or consumption. They could not, in any meaningful way, distinguish between “Skunk” and other high-THC strains.

Conveniently, Skunk #1 — the strain at the heart of Sativex development — is known to express THC levels between 14% and 18%.

Shortly after Blair’s comments, he directs the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) to launch a review of cannabis.

...

To Note: I remember this vividly — a BBC News report in 2005 that immediately zeroed in on “Skunk”. I ended up ranting to my housemates about it.

Back in 1998, I was living in Germany. Most weekends, I’d cross the border into the Netherlands and visit coffeeshops in Groningen. The menus told their own story: Skunk variants made up just over half of what was available.

From 2001 through to Blair’s 2005 announcement of a U-turn, I was growing cannabis and speaking regularly with other growers.

Skunk? Nowhere. It was considered a blast from the past — nostalgic, not notorious. And that’s how I knew something wasn’t right.

When ‘Skunk’ became shorthand for any cannabis over 14% THC, it wasn’t just lazy — it was strategic. It was narrative.

Outside of lab conditions, or a grower’s word and an internet forum, there was no reliable way for the public to judge cannabis strength.

But under the same conditions, if someone did get hold of verifiable Skunk #1, they’d quickly find it averages around 14% THC.

...

2006:

January: the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) responded to Tony Blair’s request to review cannabis classification. Their conclusion was clear: cannabis should remain a Class C drug. They also noted that they were unable to verify any widespread public concern.

Just seven days later, however, the MHRA created a yellow card monitoring list for CBD — triggered by two fatalities attributed to Sativex.

June: Professor Guy filed a patent — later withdrawn — which proposed the use of CBD as both a supplement and a cosmetic.

...

To note: The phrase "real public concern" begins to appear in political language around this time. While not always formally cited, it seems to evolve naturally from terms like “public outcry” — as seen in the Independent article covering Blair’s 2005 cannabis U-turn.

That linguistic shift is subtle, but important: it reframes public reaction as justification for policy, even if the evidence base is limited or manufactured.

That same framing is used again in 2007, and possibly earlier. I recall seeing “real public concern” used in documents relating to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 — but frustratingly, I’ve been unable to relocate them.

The issue is this: the government rarely engages the public in open dialogue around drug policy, so the question becomes:

How does it determine when a “real public concern” exists?

I suspect it's a rhetorical device, intended to justify legislative change — a public narrative driver, not a public mandate. That would certainly explain the timing and phrasing used across 2007–2008.

But something else unusual happened in early 2006.

Just seven days after the ACMD reported no public concern over cannabis, the MHRA created a yellow card list for CBD, citing two deaths attributed to Sativex. That’s notable because Sativex — a 1:1 THC:CBD extract derived from Skunk #1 — isn’t CBD isolate. It's a whole cannabis-based medicine.

Yet instead of adding those incidents to the long-established Cannabis sativa list, the MHRA began building a new list specifically for CBD — essentially carving out a separate safety profile based on incomplete causality.

According to a 2025 FOI from the MHRA, causality wasn’t verified. In other words, the fatalities could have been due to other factors entirely.

Why does this matter?

Because it shows how Sativex — a pharmaceutical product with two known cannabinoids — became the foundation for adverse event tracking against CBD alone. That’s a questionable move if your intent is clarity. But a logical one if your goal is to start reshaping public and regulatory perceptions around cannabinoids.

It raises a further question:

Was Sativex, or a variant of it, ever intended to be marketed as a supplement?

At this point, Epidiolex hadn’t yet entered trials (that came in 2012). But we know the University of Reading was already researching cannabinoids — including CBD — from as early as 1996. We also know their relationship with GWP was underway, if not formally documented.

Reading houses food and supplement-focused departments. They helped form the FSA. They had expertise in cannabinoids beyond THC. It’s not a stretch to suggest that Epidiolex’s pathway may have been shaped by food research frameworks as much as medicinal ones.

If that’s the case, and the groundwork for a CBD supplement strategy was being laid this early, then the lack of declared interests by academics on regulatory panels becomes a far bigger issue — one we’ll fully explore in Part 2.

...

2007:

February: GW Pharmaceuticals announce a research partnership with Otsuka Pharmaceuticals and the University of Reading. This marks the formalisation of an academic-commercial alliance that had already been developing for several years, particularly around the study of non-THC cannabinoids like CBD and CBDv.

July: Gordon Brown becomes Prime Minister and quickly echoes Tony Blair’s, citing a “real public concern” about stronger forms of cannabis — specifically Skunk. The phrase had evolved from “public outcry” in 2005 to a more formalised narrative device by this point.

During a parliamentary debate, then–Shadow Leader of the House Theresa May remarked:

“It was the present Government who reclassified cannabis from B to C in the first place, but we will support their U-turn.”

This cross-party consensus around the dangers of so-called “Skunk” helped to cement the term as a political tool, decoupling it from its original strain-specific meaning.

...

To note: Here’s what’s been laid out so far:

Waldegrave was the architect of the PPP.

Boateng was the facilitator.

Williams provided legal oversight.

And the PPP itself was signed off under Blair’s government.

What hasn’t been explored in depth — yet — is that Gordon Brown, as Chancellor, would have had to sign off on the financial mechanisms behind the PPP before becoming Prime Minister. So it’s telling that within days of stepping into the role, he echoed Blair almost word-for-word.

That’s especially notable given the focus on Skunk, which by 2007 was even more obsolete than it had been in 2005.

And when it comes to PPPs, Brown’s track record isn’t exactly without controversy.

This won’t be the last time in this timeline that a new Prime Minister moves quickly on cannabis or CBD policy, days after taking office.

We won’t go too deep into Theresa May just yet — though she emerges as one of the most significant players in this entire timeline.

Still, even in 2007, you can see her waiting in the wings, offering up piecemeal support for the government’s reclassification of cannabis — as if preparing for a more direct role.

...

2008:

February: The Police Federation and the Conservative Party both announce unequivocal support for the reclassification of cannabis.

This is deeply concerning when viewed through the lens of what will be discussed in Part 2 regarding Directors of Policing, and how both Labour and the Conservatives have used “Skunk” as a political prop to justify cannabis legislation.

It becomes even more troubling when considering that several Police and Crime Commissioners in 2025 have publicly supported calls for cannabis to be reclassified as a Class A drug, claiming it’s “worse than crack cocaine or heroin.” Some police forces have even declared the formation of specialist departments dedicated to cultivating seized cannabis that hasn’t reached full maturity.

GWP receive a second batch of cannabis samples from the Home Office.

The 2008 Home Office Cannabis Potency Report features images from Dr David Potter, whose PhD — sponsored by GWP through King’s College London — relied on these samples. The photos clearly show that the samples were anything but “small-scale.”

The 2004 sample batch (approx. 500 samples) marked the beginning of Potter’s PhD project, which aimed to catalogue cannabinoid profiles and assess the medicinal potential of various strains. His PhD was completed in 2009 and included consultancy and materials from Hortapharm — the same company that licensed a Skunk #1 clone to GWP for the development of Sativex. Hortapharm also maintained a UK office between 2004–2010.

Potter received the 2004, 2008 , and 2014 Home Office samples. In 2018, Dr Maria Di Forti was in receipt of the samples, however, her previous work in 2008 suggested she had access either to Dr Potter's data in 2008, or the samples directly.

Di Forti’s academic focus is largely on Skunk and psychosis, which strongly suggests she would have known that GWP were cultivating Skunk #1, and that cannabis above 14% THC was being misrepresented wholesale — to GWP’s benefit.

One question remains though:

Why was Dr Potter in receipt of the 2014 samples when his PhD was completed in 2009, and was GWP still sponsoring research on seized cannabis at that time?

I say 'research' there, but further in you'll see that it's not the only reason why the Home Office was providing samples to GWP past 2008.

May: The ACMD again advise against reclassifying cannabis from Class C to Class B.

No genuine public concern was found, beyond the government’s own assertions.

But this raises a valid question:

Why ask for ACMD’s advice if you’re going to ignore it anyway?

And another:

If cannabis was really “lethal,” shouldn’t it be placed in Class A instead?

The only evidence to suggest cannabis lethality comes from the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme — which, as noted, is based on unverified causality and highly suspect classifications.

June: The Home Office confirms that cannabis was reclassified due to “mental health concerns,” not lethality.

The only scientific opinion that the ACMD received about THC strength, low CBD, and psychosis risk came from Dr Potter, who was listed in the ACMD’s report as an employee of GWP.

To recap:

Data came from Home Office–seized cannabis,

Given to Potter for his PhD,

Sponsored by GWP,

Whose co-founder, Prof. Guy, admitted in A Worthwhile Medicine that GWP were managing the Home Office,

While Gordon Brown ordered ACMD’s advice to be ignored — a move that directly benefited GWP.

...

To note: The report regarding the samples in 2014 suggests that analysis was done to determine CBD levels in seized cannabis, whereas in 2008, the lack of CBD was more of a passing comment—although a significant one, since it was noted that this had been discussed with the ACMD.

But the report on the 2018 samples raises serious alarm bells when considered alongside Dr. Potter's photos in the 2008 Cannabis Potency report.

Dr. Maria Di Forti, who received the 2018 samples, stated that only 0.25g was tested per sample (out of 500) because it best represented what is found in a spliff.

So when we see Potter’s big photo in the 2008 report, a question needs to be asked:

What happens with the rest?

Did Potter process the entire batch for his PhD?

If so, the friends he thanks in his thesis for allowing him to process CBD hash in their kitchen must have had a very large kitchen.

As for the timeline: from here, everything is Skunk-driven. And in light of Guy's quote from A Worthwhile Medicine, the question becomes:

How much of that narrative was orchestrated by him?

We are effectively discussing a battle over definition:

Skunk is bad — but medicines made from Skunk are safe.

So, when does that narrative fall apart?

Is Sativex still made from Skunk #1, or is it now made from “Skunk”?

What about Epidiolex? Is it primarily made from the crops grown by British Sugar, or is there Skunk in that, too?

And a further question worth raising:

Out of GWP's 148 patents, how many of them have been filed as a result of analysis on what is, effectively, a public resource?

Because that’s how those samples should be seen.

The Home Office would have known that the samples—which were clearly more than a £10 bag—were being used for research by a GWP-sponsored scientist. Any discoveries or uses would ultimately benefit the sponsor, who already had a working relationship with the Home Office.

The conflict is glaring: the Home Office allowed itself to be managed, as Prof. Guy admits, and that management wasn’t in the public interest. It resulted in the effective harvesting of the public for illegal material, all for corporate gain.

There’s a further ethical concern: some of that cannabis would have come from individuals cultivating or possessing it for medicinal need—people who received criminal records for doing so, even as their seized product was repurposed to benefit a private company.

So consider this:

A company, controlling the Skunk Narrative to protect ownership of Skunk #1, gaining access to public resource, while the original owners of that resource are criminalised.

How can that possibly be in the public interest? Let alone be allowed to continue?

Worryingly, the four known batches are likely not the full extent of what was transferred.

But it is clear that a lot was. Likely, tons. Which echoes a remark quoted by Prof. Guy in The Medicinalization of Cannabis, from then Chief Inspector of the Home Office Drugs Inspectorate (HODI), Alan Macfarlane:

You'll need tons of it

The sample dates are significant:

2004: Potter begins his PhD, focusing on CBD.

2008: Potter nears completion. His data justifies the reclassification of cannabis on the basis of its low CBD content.

2014: Epidiolex enters Phase II trials.

2018: Samples provided prior to Epidiolex's authorisation in the US and EU, and before the UK legalised medicinal cannabis via a policy vehicle (see Part 2) that favoured Epidiolex.

According to the 2008 Home Office Cannabis Potency report, 22 police forces provided samples. We must assume these were sent directly to GWP, and Potter’s photographic evidence confirms they weren’t small quantities.

Shall I quote Macfarlane again?

So, here are two key questions given the timeline:

When will the public see a return?

This PPP has been running for over 25 years. People are still being arrested. And based on Jazz Pharmaceuticals’ submission to the 2022 Home Affairs Committee’s review of recreational drug use—a year after they acquired GWP—the relationship with the Home Office remains strong.

All of this has contributed to patent filings, most likely based on analysis of public resource, while the public have been excluded from any conversation about how that resource was accessed.

And that resource seems to have been used to develop a specific product—perhaps even providing the raw material at critical times.

Frankly, we’re owed something.

When will the public see convictions overturned?

There is clear injustice here, and it starts with Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

They allowed the PPP to exist and set it on a course that brings us to the present.

While Theresa May and Victoria Atkins may be seen as modern enforcers of cannabis policy, they were merely driving forward the intent laid out by Paul Boateng in 1997—after Blair and Brown ceded cannabis to GWP.

And then they misrepresented the public by citing a “real concern” that didn’t exist.

That is what the Skunk Narrative conceals:

Corporate control

Political complicity

Initiated and protected by a false narrative

Call to Action

There must be a full investigation into the use of the Skunk Narrative in the UK.

That investigation should focus on:

All corporate relations with the Home Office relating to cannabis

Influence exerted by the Home Office on other government bodies concerning cannabis or hemp (outside of recreational use)

Any directive by the Home Office to police forces to intensify cannabis clampdowns prior to samples being sent to GWP or its affiliates (see Part 2)

A review of how and when GWP were awarded a license to grow cannabis, and who first proposed government-funded research

Disclosure of the individual who initiated that proposal, particularly if they later held shares in GWP at the time of Jazz Pharmaceuticals' acquisition

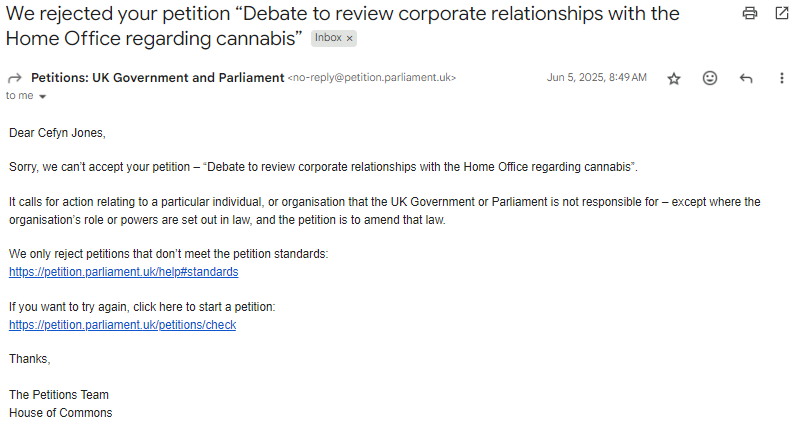

A petition calling for a debate on these issues was recently rejected, and no response has been received despite appeal.

Even more worrying, the Petitions Committee has not yet added the rejection to the public list—25 working days after the decision.

Final thoughts

What created the need for the Skunk Narrative?

In 2005, people already knew GWP owned Skunk #1. They knew the company had a close relationship with the Home Office, and that vested interests were being protected.

So changing the public perception—from a named strain to any cannabis over 14% THC (a figure Skunk #1 conveniently averages)—wasn’t regulation. It was subterfuge.

And it continues, every time the media echoes a narrative that is now two decades old.

I want to close this part with a return to that original article on narrative fatigue.

According to Making Sense of Politics: What Does Narrative Mean?

In Part 2, I’ll explore how this fatigue may stem from the protection of CBD Policy, and the impact this has had on businesses and consumers in both medicinal and non-medicinal spaces—as well as those who simply enjoy a bit of origami (paperwork!).

But here, fatigue can go one of two ways:

Either you accept that ‘Skunk’ now means any cannabis above 14% THC — and that the narrative exists to protect GWP’s PPP,

Or

You recognise that this fixation continues to criminalise users, damages UK cannabis credibility abroad, and needs to be directly challenged.

There must be a full, independent investigation into the deliberate use of the Skunk Narrative in UK drug policy—and into the political & commercial interests it served.

By the way, Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome is the US version of the Skunk Narrative. You heard it here first.

Comments